Reading with Children

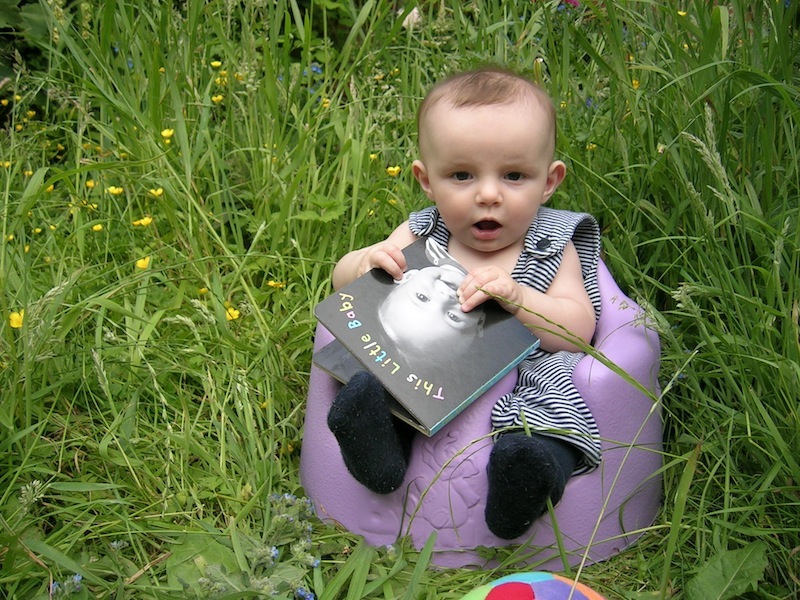

Everyone knows the benefits of reading to babies and toddlers, right? Health visitors hand out Bookstart packs in the UK almost as soon as your child is born, libraries run all-singing, all-dancing, glue & glitter sessions for families; Dolly Parton posts books monthly to children in the UK, the US, Canada and Australia. And the results from research is overwhelming: a child is never too young for a book.

Everyone knows the benefits of reading to babies and toddlers, right? Health visitors hand out Bookstart packs in the UK almost as soon as your child is born, libraries run all-singing, all-dancing, glue & glitter sessions for families; Dolly Parton posts books monthly to children in the UK, the US, Canada and Australia. And the results from research is overwhelming: a child is never too young for a book.

But when should we stop reading to children?

I stopped when Lyra was about 6 and reading herself. It wasn’t a conscious decision, I was just busy and she was really into books about fairies and princesses, particularly rainbow magic princess fairies, which wasn’t really my thing (still isn’t). But then I read Jim Trelease’s Read-Aloud Handbook and I expect I’ll be reading to Lyra until she begs me to stop.

Why read to children?

Pleasure

‘Children who are read to at home read more on their own’ (Krashen 2004 pg. 77). Reading to children fosters a love of books that does not come from direct instruction or learning phonics. Children who read tend to be more successful at school: reading impacts vocabulary, cognitive growth, writing style, grammar, spelling, general knowledge, attention span. Sharing books with a child also involves emotional engagement. There is a well-documented link between illiteracy and poverty.

Alternate Worlds

Books allow us to explore worlds and situations we rarely, if ever, meet in daily life. They can help develop empathy and offer an environment in which we can explore and express our own thoughts, feelings and questions.

Vocabulary

In general conversation, with adults or children, we tend to use around 10,000 words. In fact ‘83% of the words we use in normal conversation with a child come from the most commonly used thousand words, and it doesn’t change much as the child ages’ (Trelease 2006 pg. 16). Studies of the language of TV and ordinary conversation found that ‘95% of the words used were from the most frequent 5,000 words in English’ (Krashen 2004 pg. 143). Children’s books contain a much higher number of uncommon words (30.9 per 1,000) than adult-child conversations (9 per 1,000 words) or adult-adult conversations (17.3 uncommon words per 1,000) (Trelease 2006 pg. 16).

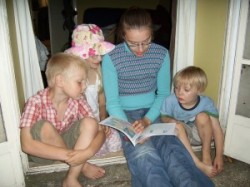

What to read to children who can read?

Shared reading (reading aloud) should be an enjoyable experience for all, it’s important that you’re as enthusiastic about the book as your child. Although magic rainbow fairy princesses wasn’t doing it for me, Eva Ibbotson’s tales of trolls, ghosts and witches and fantastical creatures were brilliant for both of us. A child’s listening skills are more developed than their reading skills until at least 13 or 14 years old (Trelease 2006 pg. 37), they can handle listening to books far more advanced than those they would choose to read to themselves.

What else can I do to encourage my child to read?

Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) is very important. Studies have shown that SSR has a huge impact on academic ability. Children read more when they see other people e.g. teachers, parents, reading (Krashen 2004 pg. 85). Trelease advocates ‘the Three Bs’ – Have books in the home. Ownership of books has been shown to be important to children’s development. Allow children to choose their own reading matter, comics or magazines they love will do more for their reading than chapter books they hate. – Have book baskets or book shelves within easy reach. Studies have shown that print spread throughout the house has a greater impact on reading than when confined to a particular place (Trelease 2006 pg. 36). – Give your child a bedside lamp and allow some time before lights out.

Further Reading

‘The Read-Aloud Handbook‘ by Jim Trelease, pub. Penguin. I can’t recommend this book highly enough. It is essential reading for parents and teachers. It’s very readable, packed with anecdotes and supported by up-to-date research. The book covers all aspects of reading aloud to children and the benefits of silent reading, it also includes an extensive booklist of recommended books for kids. Although it is written for an American audience, I believe there is a UK edition available. Also, have a look at Jim Trelease’s website. ‘The Power of Reading. Insights from Research’ by Stephen D. Krashen pub. Heinemann. Krashen is a big name in Linguistics and this book is a slightly more scholarly investigation into the benefits of reading, looking at reading at home and in-school reading programmes. He discusses the benefits of reading comics, reading and television, the impact of reading on writing and reading for EFL learners among other things. ‘The Reading Bug‘ by Paul Jennings pub. Penguin. Jennings is a best-selling children’s author and teacher. His writing about phonics instruction is particularly interesting. The American Read Aloud website also has a lot of information.

Sounds reasonable! I deitnfiely think that some practice of speaking is essential in order to gain confidence in using language we’ve already learnt, but as we learn L1 by generally receiving first, it makes sense to have to listen and read before spending huge chunks of lesson time on it. I’ve felt bad for not doing more communicative things in class with my adult pre-ints, but it is like drawing blood from a stone when I do because they simply do not have the language resources to make a lot of meaningful output. I’m pleased that they manage to express themselves as they do, but they deitnfiely need more input. My young pre-ints (11-14) are very good at speaking and making themselves understood (though they make significant grammatical errors), much more so than adults of the same level, and they kid me into thinking they are more competent than they are. But when I give them a simple enough reading comprehension, they simply can’t detect the message contained in the text. Then they make mistakes in tests that show it’s not all gone in yet.I wouldn’t go as far as to take away productive stages in my lessons as I think that doing is quite important from an early stage, but reading is essential. And obviously listening, but I hate listening from bad experiences as a learner, so I feel like a hypocrite when I talk about listening.