British Novels Which Have Added To The English Language

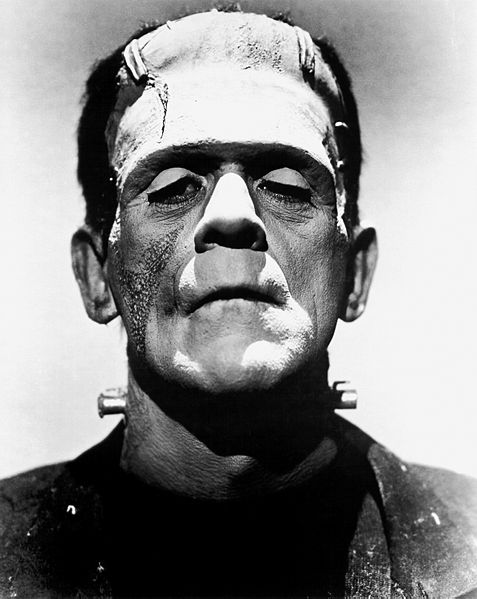

No. 5 Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

An enduringly popular gothic horror story published in 1818. It has been claimed that this was the first proper science fiction novel. It’s the story of a sea captain who sets out to explore the North Pole and meets a chemist called Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein tells him of a creature he made and brought to life which turned out to be a hideous, murderous monster (or possibly just very misunderstood). You may prefer to read an abridged version as the original uses rather a lot of old-fashioned English.

Themes Quest for knowledge, dangers of knowledge, nature vs nurture.

Words & Phrases

Franken /ˈfʀaŋkən/ (prefix) indicates artificiality, or a combination of disparate elements, often terrifying or unattractive

e.g. Frankenfood often used to refer to genetically modified foods

Frankencat a cross between two big cats, usually a lion and a tiger A coalition of US conservation groups has launched an attempt to outlaw the breeding of so-called frankencats.

Frankenstorm a very large and dangerous storm formed by a combination of storms; in particular, a combined storm formed when a hurricane encounters other winter storms Sandy is forecast to combine with two other storms in the coming days, creating what the weather service has called a “Frankenstorm”.

Frankenword a word formed by combining two, or more, parts of other words, e.g. Obamista, Clintongate

Excerpt from Chapter Four

I see by your eagerness, and the wonder and hope which your eyes express, my friend, that you expect to be informed of the secret with which I am acquainted; that cannot be: listen patiently until the end of my story, and you will easily perceive why I am reserved upon that subject. I will not lead you on, unguarded and ardent as I then was, to your destruction and infallible misery. Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.

When I found so astonishing a power placed within my hands, I hesitated a long time concerning the manner in which I should employ it. Although I possessed the capacity of bestowing animation, yet to prepare a frame for the reception of it, with all its intricacies of fibres, muscles, and veins, still remained a work of inconceivable difficulty and labour. I doubted at first whether I should attempt the creation of a being like myself, or one of simpler organisation; but my imagination was too much exalted by my first success to permit me to doubt of my ability to give life to an animal as complex and wonderful as man. The materials at present within my command hardly appeared adequate to so arduous an undertaking; but I doubted not that I should ultimately succeed. I prepared myself for a multitude of reverses; my operations might be incessantly baffled, and at last my work be imperfect: yet, when I considered the improvement which every day takes place in science and mechanics, I was encouraged to hope my present attempts would at least lay the foundations of future success. Nor could I consider the magnitude and complexity of my plan as any argument of its impracticability. It was with these feelings that I began the creation of a human being. As the minuteness of the parts formed a great hindrance to my speed, I resolved, contrary to my first intention, to make the being of a gigantic stature; that is to say, about eight feet in height, and proportionably large. After having formed this determination, and having spent some months in successfully collecting and arranging my materials, I began.

No one can conceive the variety of feelings which bore me onwards, like a hurricane, in the first enthusiasm of success. Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world. A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs. Pursuing these reflections, I thought, that if I could bestow animation upon lifeless matter, I might in process of time (although I now found it impossible) renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.

Also see: This has been made into film many times, have a look at ‘Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’, 1994, starring Kenneth Branagh, Robert DiNero, Helena Bonham Carter, John Cleese.